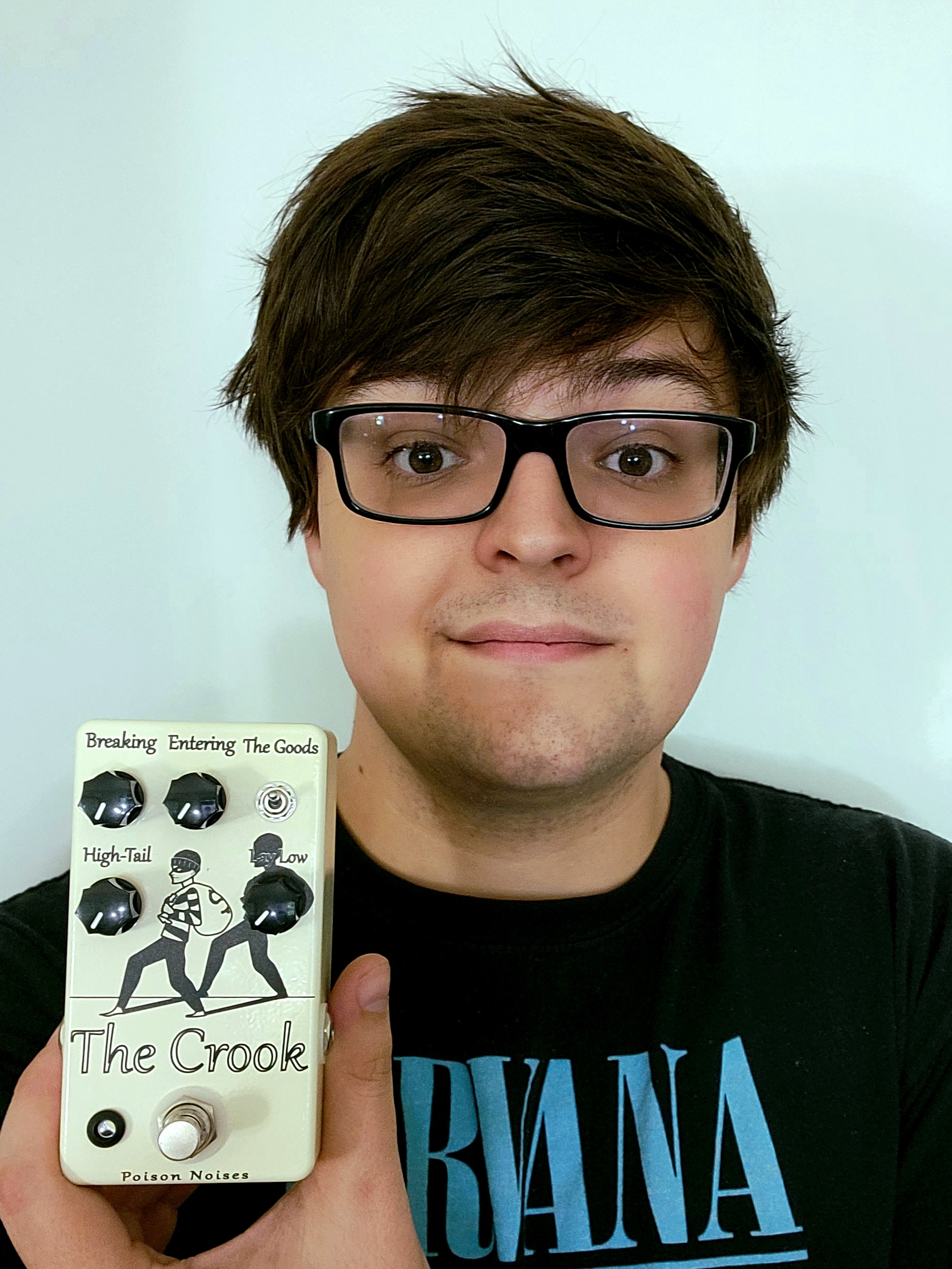

Jordan Withers

The first widely marketed pedal was Gibson’s Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone, famously used by Keith Richards on the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” In the 60 years since the Maestro was introduced, pedals have continually morphed to where you can do exponentially more with them than play that iconic hook. And in recent years the pedal market has exploded, with new, boutique manufacturers entering the market all the time. With this has come a rise in the amount of pedal dealers in MI.

“Back in the ’90s, there were 10, 15 dealers that really were selling the bulk of the boutique stuff,” said Heath Berkowitz, owner of Boston Guitar, a store in West Bridgewater, Massachusetts, stocking thousands of pedals. “Now there are probably 200 that are really the top people who sell all these boutique or whatever you want to call them pedals.”

Martel Music Store in Plainville, Connecticut, is one of the newer entrants to selling pedals. Having worked in MI since 2004, both on the supply side and the retail side, in 2017, Corey Martel started his own store with his wife, and it’s taken off.

“It’s been pretty steadily growing every year — 66 percent year two, 138 percent year three, and just this year, so far, we’re already up 35 percent over last year.” According to Martel, the pandemic led pedal sales to thrive beyond his wildest imagination; the store has seen a 200 percent increase there and added seven lines.

But the pandemic hasn’t just boosted pedal sales. It’s actually created new pedal manufacturers. Poison Noises is a handmade guitar and bass effect pedal company based out of Schenectady, New York. Its two founders — in fact only two employees — are Jordan Withers and Connor Taylor.

When the pandemic started, both were working at Guitar Center and were furloughed and went on unemployment. Withers had already been working on pedals in his spare time and in quarantine he really applied himself to their development. In May 2020, Guitar Center brought them back and to Withers this didn’t feel right.

“I didn’t feel comfortable thinking that selling guitars was considered essential work that early into the quarantine phase,” he said. Meanwhile, Taylor felt Withers was really onto something with his work, Withers said. “I was like, ‘I’m just going to go at this thing full bore and try to figure it out and just put it all on the table and see if I can actually make a living doing this.” He quit Guitar Center and Taylor, who handles the business side of the company, followed suit in July of this year. And so Poison Noises was born.

“So far it’s been a wild success,” Withers said. Poison Noises is at retail locally and is looking to talk to new dealers, starting with Sweetwater.

Berkowitz broke down the process of how pedal manufacturers and retailers connect based on his considerable amount of experience doing it. “What I’ve always seen in the pedal business is that the guys who are the best at making great gear are not usually the best at customer service,” he said. “A lot of times they have no idea how to talk to somebody; how to maintain a relationship that might be important to them. A lot of what I do is getting in on the ground floor with the company.”

He relayed a recent experience in which he approached a pedal manufacturer he wanted to work with, but the owner expected to give any dealer just a 15 percent discount off his direct sale price.

“I go, ‘That’s not going to happen. There’s no dealer in their right mind that’s going to buy it. We have a million pedals to sell. I don’t need yours.’”

Berkowitz and the company owner were able to come to a compromise at 25 percent. But he said what he’s seen happen is after manufacturers sort out with him how to sell to retailers, they then replicate this arrangement with many other dealers, then get confused when their sales numbers decline with him.

“Six months down the road he’s like, ‘Hey, you’re not selling as many pedals as you were.’” he said. “I’m like, ‘Well, yeah, you opened with 10 other dealers. I never said you couldn’t, or that I had a problem with it, but that’s the evolution of it.’”

Pedal Addiction

So, if pedal sales are exploding, who’s buying them? Martel defined his customers as 80 percent 18- to 45-year-old men. Berkowitz confirmed this age range. “Honestly, it’s young and old,” he said. “It’s people [who] can play and people [who] can’t. One of my better customers doesn’t play in a band, and he buys a pedal a day. It could be an addiction, a serious addiction. I’m not even joking.”

Jean-Claude Escudie, director for premium stringed instruments and pedal effects at Guitar Center, broke down what he sees as the three types of pedal customers. He said there are people who want to duplicate an imagined sound. Then there are customers who have the desire to create something unexpected. “So, if you were to plug a guitar in with one pedal, five minutes later you’d be playing something very interesting,” he said.

Then, Escudie pointed to customers wanting pedals to emulate their idols, citing Jimmy Page as an immediate example. Berkowitz sees this too but has some skepticism on the topic. “The amount of people, even now, that want to get David Gilmour’s tone is crazy,” he said. “Do you know how many people come in my store and go, ‘I want the stuff Stevie Ray Vaughan used?’ And for years and years I’ve been saying the same thing. ‘I’ll sell you that, but you’re not going to sound like it.’”

Ric Tomasi, owner of Guitar Pedal Shoppe in Plymouth, Massachusetts, echoes this in defining his customers. Interestingly, he cited the same two guitarists. “Sometimes it’s just someone that is looking to mimic an idol of theirs, such as, ‘Hey, I want to sound like David Gilmour or Stevie Ray,’” he said. “There’s also the customer that artistically is the opposite of that and wants to create their own sound, which I encourage. Because at the end of the day, they’re not going to sound like their idol, even if they have their idol’s rack.”

Poison Noises’ pedals are intended to encourage creativity. For example, one of its pedals is called Tractor Beam and its knobs are labelled Invade, Warp, Abduct and Probe. In the middle of a pink pedal is a drawing of a spaceship pulling a cow upward with a tractor beam. This doesn’t explain what this pedal does. Withers said this has led musicians to give him the feedback, “I don’t know what these do.”

“Our answer is always, ‘Well, you’re a musician. You’re supposed to experiment. Turn the knobs. Figure it out,’” he said.

Matt Duncan, director of merchandising for guitar amps, effects and accessories at Sweetwater, said the quarantine encouraged guitarists to take this approach. “Being stuck in your house for a year, as everybody was, I think that really allowed people to just experiment more and to really start to fine tune and hone in on what they’re wanting to hear as opposed to a work-mandated thing, like ‘I have to sound like AC/DC because I play in an AC/DC cover band,’” he said. “We’re always chasing a hero from yesterday on tone. It’s only a very few number of artists that are out nowadays that really have a tone that is theirs, that they created themselves, that isn’t a hybrid of Jeff Beck or Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton or somebody in the past.”

Flipping Out

Eric Thompson of Pedals Music in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, outlined why it’s more fun to work with small, boutique pedal manufacturers than the larger ones. You’re under less financial pressure. “I worked for a store that did all the big brands and those big [companies] just make you spend so much to carry their product,” he said. “These small pedal companies, you call them up and they may only have five or six pedals in their line. They’re like, ‘Yeah, just order one each,’ and it’s cool, and you get a whole new line of stuff that’s fun and cool to look at.”

But Jeff Slingluff, strategic product manager at Boss, pointed out some potential issues with small, boutique pedal manufacturers. “There could be an appeal to something that was done by a guy who knows a guy who works out of his garage and did something by hand, which has got a nice, fun, unique appeal to it,” he said. “But for a touring artist those can be really problematic. They can’t get service for them, they fall apart. They don’t handle TSA very well.”

As someone who travels on business with pedals, Slingluff described TSA as the bane of his existence. “They have taken every single pedal off my pedalboard on several occasions,” he said. “So it shows up and there’s the nice little note and literally every piece of dual lock that I’ve got on there, they’ve ripped off. They’ve disconnected every single cable in the process. I have met some touring artists who carry their pedals freeform in a bag because they’ve been screwed over by TSA so many times.”

This is because, when X-rayed, a pedalboard looks a lot like a bomb. And homemade pedals may look like that even more so.

Regardless, demand for boutique pedals is only growing, and with that comes some odd fluctuations in the market. Pedals have always been collectable, but limited run pedals getting flipped on eBay and Reverb for multiple times their original price is happening with increased rapidity. Joel Korte at pedal maker Chase Bliss has experienced this, and didn’t like it.

“Unfortunately, we’ve been a part of several conversations when it comes to that and not really by choice,” he said. “We’re trying to avoid it now. I prefer that the stuff that we make gets used and people use it for creative purposes and it doesn’t just sit up on a shelf or in a box somewhere. But you only have so much control over that. We’ve done a few limited runs and it hasn’t been very fun. That just takes over the conversation.”

On flipping new pedals, Berkowitz wished that pedal manufacturers had better control over such situations. “I feel like there are many reasons why flipping happens but [they] are usually related to supply and demand,” he said. “Availability, underestimating demand, COVID-19, shipping issues — it’s all a problem.”

Even Boss has dealt with flipping. “We made it a limited run of the Tone Bender, but in a Boss pedal,” Slingluff said. “We only made around 3,000 units for the entire world. The reason we only made 3,000 units — it wasn’t a publicity stunt — was because we were using vintage parts. When we released it, the street price was $350. Within hours, they were all sold out from every dealer that had them. Those units started going up for $3,000.”

Martel has dealt with pedals so limited and in such high demand that he has to maintain a spreadsheet of customers who want them and selects who gets to buy them via a randomized lottery system. He’s handled pedals under embargo, where he learned they were being released on a Saturday and wasn’t allowed to announce their availability until Tuesday, but was already getting messages from customers about them on Monday. “I went, ‘How the hell do they know this?’” he said.

Martel saw a situation like this recently with the Third Man Hardware’s x Coppersound Triplegraph Pedal. He requested 25. “They were generous enough to double my order,” he said. “They sold within two hours of me announcing them and it was complete chaos. My website almost crashed. It was pretty wild.”

The Triplegraph initially cost $400, but according to Martel it was soon being flipped for as high as $1,500. He said, “It gets a little dirty, a little ugly out there.” MI